For a disclaimer, as a person of faith, I’m in agreement with almost nothing of the US White Evangelicals’ religious teachings. I’m not an expert of this subject, however, I’m curious as to how the Evangelical thinking is influencing the politics of today. I’ve had to rely on a myriad of sources including my daughter, an ex-Evangelical, to be able to write about this subject.

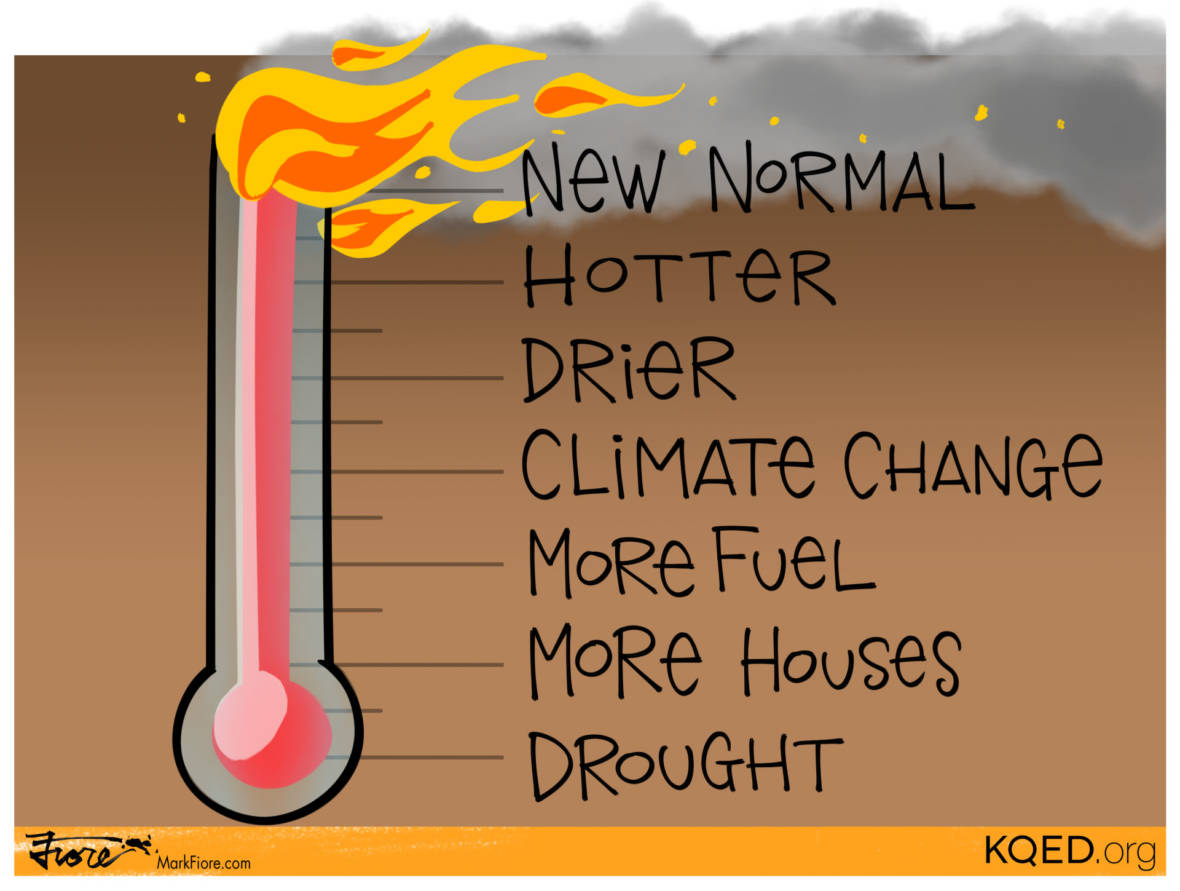

This is my sixth post in a series on this subject of White Evangelicals and their effect on US culture, especially at White House. One example has to do with the president not paying a price for being a ‘climate change denier because his thinking reflects that of Evangelicals.

The White Evangelism community in the USA has become powerful, even though its population comprises a minority at about 26% of the US population who self-identify themselves as Evangelicals; however, its members have voted in 2016 for the republican President Donald Trump by a margin of 80%, plus, they continue to approve of his presidency at rates that exceed 70%. They add up to over 35% of the president’s base of voters.

It should be obvious that they would enjoy an out-sized level of influence over President Trump, as they are the most reliable faction within his base of voters, to where he would be highly motivated to please them. It doesn’t help that this community is entrenched in the belief that the republican President Donald Trump has been sent by God to represent and champion their causes.

In addition, the president relies on a group of Evangelical Christians for spiritual guidance.

See: : Evangelicals Have Out-Sized Influence In President’s Crafting Of US Foreign Policy

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/What-If-Its-A-Hoax-56a74f4c5f9b58b7d0e8f300.jpg)

As per 9/1/2015 Sage Journal article, “Why conservative Christians don’t believe in climate change” by Bernard Dailey Zaleha and Andrew Szasz, “American Christians have become increasingly polarized on issues of climate change and environmental regulation. In recent years, mainline Protestant denominations and the Roman Catholic Church have made explicit declarations of support for global climate action. Prominent Southern Baptists and other evangelical Protestants, on the other hand, have issued statements that are strikingly similar to the talking points of secular climate skeptics, and have attempted to stamp out “green” efforts within their own ranks.”

“An analysis of resolutions and campaigns by evangelicals over the past 40 years shows that anti-environmentalism within conservative Christianity stems from fears that “stewardship” of God’s creation is drifting toward neo-pagan nature worship, and from apocalyptic beliefs about “end times” that make it pointless to worry about global warming. As the climate crisis deepens, the moral authority of Christian leaders and organizations may play a decisive role in swaying public policy toward (or away from) action to mitigate global warming.”

“In what is certainly the most famous essay ever written about religion and the environment, the historian Lynn White Jr. argued that medieval Judeo-Christian ideas were at “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis” (White, 1967). Citing passages in the Bible that separate God from nature and grant humanity dominion over all, White wrote: “Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen.” He also opined that much, if not most, environmental degradation is directly traceable to Christianity’s radical anthropocentrism (White, 1967: 1205).”

“Recent research seems to confirm White’s rather bleak assessment of the relationship between Christian beliefs and environmental attitudes. University of Cincinnati political scientist Matthew B. Arbuckle and Georgetown University public policy expert David M. Konisky recently reported (forthcoming) that American Christians, as a whole, have lower levels of environmental concern than do non-Christians (Jews, people of other faiths, and nonbelievers). Arbuckle and Konisky also found, tellingly, that the higher the level of religious commitment (as measured by self-reports of religion’s personal importance, frequency of religious service attendance, and frequency of prayer), the lower the level of environmental concern.”

See: (Clements et al., 2014).

“But, then, how are we to make sense of declarations from the mainline Protestant faiths in the United States—Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, and Lutherans—proclaiming that God wants humans to care for creation? And what about Pope Francis’s powerful new encyclical on climate change, “Laudato Si”? Yes, some Christians do believe that humans are separate from, and superior to, nature, and that God has given humans license to multiply without limit and to dominate and exploit the rest of creation. But it is also obvious, both from their own statements and from opinion surveys (see Figure 1), that other Christians, though they have read the same Bible, have come to radically different conclusions about what God wants and expects of humans.”

“American Christians have become increasingly polarized on issues such as climate change, with the most conservative Christians—that is, Southern Baptists (America’s largest Protestant denomination) and other evangelical Protestants—expressing the most anti-environmental attitudes and attempting to suppress “green” efforts that have arisen in their own ranks. The reasons for this environmental backlash include conservatives’ suspicions that “stewardship,” improperly understood, smacks of neo-pagan-style nature worship and might even lead to anticapitalist sentiments. The backlash also depends on a reinvigorated belief in “end times” apocalypticism that makes it pointless to worry about global warming and other environmental problems.”

Conservative, moderate, and liberal Christianities

“It is helpful to think of Christianity not as one undifferentiated or uniform mass of believers but as an internally deeply divided community. Princeton University sociologist Robert Wuthnow argued in 1988 that to understand differences within American Christianity one needed to look beyond denominational labels and to think, instead, of three different categories of Christians: one theologically conservative, a second quite liberal, and between them a broad swath of amorphous and ill-defined moderates (Wuthnow, 1988, 1996). All three types are present in every denomination, but not to the same degree.”

“Recent studies show that Wuthnow’s way of conceptualizing divisions within Christianity was on the mark. Some Catholics believe climate change is real and a serious problem; other Catholics don’t. Many Methodists do, but some don’t. There are climate skeptics even within the most liberal denominations. Conversely, although a large majority of evangelicals are skeptical about climate change, between one-fourth and one-third of evangelicals aren’t (Arbuckle and Konisky, forthcoming; Barna Group, 2007; Jones et al., 2014). The proportions of conservatives, liberals, and moderates within each denomination vary significantly.”

“Conservative Christians, whatever “official” denomination they belong to, constitute one of the core demographic foundations for climate skepticism—or, more properly, denialism—in the United States today Arbuckle and Konisky, forthcoming; Barna Group, 2007; Jones et al., 2014). Why? While White was right that Christianity in all its forms does, in the aggregate, suppress environmental concern, anthropocentrism doesn’t explain the obvious differences between conservative and liberal Christians on climate change. Other factors have contributed to a major shift in how American conservative Christians perceive environmental “stewardship” and weigh its importance.”

Divorced from nature

“For those not already familiar with Christian, and especially conservative Christian, metaphysical claims about the nature of God, some historical background is critical to understanding contemporary environmental debates within American Christianity. According to Hebrew Bible scholar Richard Elliott Friedman, the ancient Israelites produced the first enduring monotheism—the belief in a single god. The difference between Israelite monotheism and the pagan religions of that era was not a simply a “matter of arithmetic: one God rather than many … . Pagan religion personified [nature’s] forces, ascribed a will to them, and called them gods” (Friedman, 1995: 87). In contrast, ancient Israel, for the first time in recorded human history, conceived of a God above and beyond the now-desacralized forces of nature.”

“This divorce of God from nature had other ramifications. It allowed biblical writers to imagine that humans occupied a more exalted position in the natural order than the nature-based pagan religions conceived. One example is a passage from the Hebrew Bible’s book of Psalms declaring that God made humanity “a little lower than God,” with “dominion” over God’s creation, putting “all things under their feet, all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the seas” (Psalm 8: 6–8, New Revised Standard Version). Another Psalm asserts: “The heavens are the Lord’s heavens, but the earth he has given to human beings” (Psalm 115: 16). Environmental historian Clarence Glacken noted that one of the key ideas in the religious and philosophical thought of Western civilization, which is derived from Christianity, is that humans, sinful though they are, nevertheless occupy “a position on earth comparable to that of God in the universe” (Glacken, 1967: 155).”

“Church father, missionary, and theologian Paul of Tarsus carried forward into early Christianity this Hebrew Bible concept of human superiority to, and dominion over, the rest of nonhuman nature. In his New Testament Epistle to the Romans, Paul wrote that God had abandoned pagans because they “worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator” (Romans 1:25), thus incorporating from first-century Judaism, into movements that would eventually become early Christianity, the idea that there is an absolute separation between an external supernatural God and the natural created order, and that to venerate nature was to engage in idolatry. Crucially, this passage is one of the most cited whenever conservative Protestant Christians discuss human responsibility for the environment, and it is why the famed Protestant theologian Paul Tillich noted that, within Christianity, the term pantheist is “a ‘heresy’ label of the worst kind” (Tillich, 1951: 233).

“These ideas were uncontroversial standard Christian theology across most of American Protestantism and Catholicism until the 1960s. From medieval times to the present, there have always been minor strands of mystical nature veneration within Christianity, but none had much impact on the major denominations of European or American Christianity. Lynn White had this history in mind when he wrote his seminal, controversial essay.”

“The first major Christian response to White came from Francis Schaeffer, a then-prominent thinker within evangelical Christianity who is still widely cited. In Pollution and the Death of Man(1970), Schaeffer acknowledged the intensifying problems of environmental pollution, but denied that these problems stemmed from Christian arrogance and anthropocentrism. He affirmed that only humans were created in “the image of God” and were therefore uniquely exalted. According to Schaeffer, however, humans only held nature in stewardship for the true Owner. When we have dominion over nature, it is not ours, either. It belongs to God, and we are to exercise our dominion over these things not as though entitled to exploit them, but as things borrowed or held in trust, which we are to use realizing that they are not ours intrinsically. [Humanity’s] dominion is under God’s dominion and under God’s Domain. (Schaeffer, 1970: 51, 70; emphasis in the original)”

“This strand of Christian environmental thought became known as the stewardship school, because wise “stewardship” is its watchword. From the Cornwall Alliance on the right (Cornwall Alliance, 2009a) to Pope Francis (Pope Francis, 2015: 87) on the left, stewardship is the preferred trope for environmental care in most wings of American Christianity. But “stewardship” can be, and has been, interpreted in wildly different ways.”

“The United Methodist Church, for example, last year stated: “As a matter of stewardship and justice, Christians must take action now to reduce global warming pollution” (General Board of Church & Society of The United Methodist Church, 2014). More recently, Pope Francis’s encyclical called climate change “a global problem with grave implications” and stated that “our concerns for the environment [direct] us to be stewards of all creation” (Pope Francis, 2015). For liberal Christians, the call to be a better steward is urgent, unequivocal, of the highest priority, and not to be subject to negotiation or compromise. For conservative Christians, however, the commitment to stewardship has become increasingly hemmed in with certain reservations and qualifications.”

Southern Baptists’ version of stewardship

“The Southern Baptists’ struggle to find an acceptable definition of stewardship offers an excellent example from the conservative side. In the early 1970s, likely under the influence of Earth Day and the rise of modern environmentalism, the Southern Baptist Convention passed several resolutions on the environment. The first, passed in 1970, warned “man has created a crisis by polluting the air, poisoning the streams, and ravaging the soil” (Southern Baptist Convention, 1970). The 1974 resolution continued in a similar vein: “We have recently been made more conscious of our selfish and nearsighted use of our resources … [therefore, Christians now must] assume our individual and corporate responsibilities as faithful stewards.” The resolution “urge[d] Congress and concerned governmental agencies to take aggressive action to conserve our diminishing resources” (Southern Baptist Convention, 1974). This was a definition of “stewardship” that was practically indistinguishable from what modern environmentalists were saying: Pollution is the problem; government regulation is the answer.”

“By 1990, though, the tone had shifted. The resolution that year still condemned the sinfulness of the human race [that] has led to the destruction of the created order … as evidenced by the endangerment of the earth by pollution, human extravagance and wastefulness, soil depletion and erosion, and general misuse of creation and it affirmed “our responsibility to God to be better stewards of all of the created order.” But a new theme appeared: Southern Baptists should care for creation but “are forbidden to worship the creation” (Southern Baptist Convention, 1990; emphasis added), a point seemingly intended to distinguish Baptists from pantheistic, neo-pagan environmentalists.”

“Along these same lines, the Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission’s Policy Statement on Global Warming (Lewis, 2005) defines stewardship as lying somewhere between two extremes, “using nature without any reservations, leading to environment destruction” on the one hand, and “a pantheistic view of the world [that puts] nature at the center of the universe rather than God” on the other. Similarly, a new resolution, passed in 2006, made it crystal clear that a Christian understanding of stewardship is not the stewardship of neo-pagan environmentalists who “have completely rejected God the Father in favor of deifying ‘Mother Earth’” (Southern Baptist Convention, 2006).”

Having distanced themselves theologically from what they saw as pre-Christian religion, these two documents went on to present more purely secular anti-environmental and climate denialist talking points. The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission’s Policy Statement on Global Warming stated that “tens of thousands of scientists agree that there is no conclusive evidence for the manmade global warming theory. Records prove that climates have changed in the past without human interaction.” The statement warned that the Kyoto Protocol, if implemented, “would have disastrous effects on the economy” including job losses and increased poverty (Lewis, 2005). The 2006 Southern Baptist Convention resolution repeated climate skeptics’ favorite arguments but went even further, approvingly talking of “respecting ownership and property rights” and opposing solutions that “bar access to natural resources and unnecessarily restrict economic development.”

See: (Oreskes and Conway, 2010).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/republicans-climate-titanic-566336c33df78ce161a01579.jpg)

End times

Beyond explicit policy statements, could there be something else in Christianity that suppresses environmental concern? A trailblazing study conducted in 2014 by the Public Religion Research Institute provides a clue. Almost half of all Americans attributed the severity of recent natural disasters to biblical “end times.” Among white evangelicals, that number jumped to 77 percent (Jones et al., 2014: 23).

See: (Barker and Bearce, 2013)

Interesting stuff, Gronda.

A potentially interesting offshoot of this post (either for you or someone else) could be on how people from the same denominations, with the same leaders, reach such radically different conclusions about climate change. Take, for example, the fact that Hispanic Catholics very much share Pope Francis’ concern while White Catholics are one of the groups least concerned according to the poll.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Brendan Birth,

What an excellent suggestion. It turns out that many Black Evangelical Churches have taken a very different stance regarding climate change vs. their White counterparts. One has to wonder if they both pray to the same God and if they read the same Scriptures?.

I’ve just posted a blog on this very issue. Great minds think alike.

Hugs, Gronda

LikeLike

Yep. Absolutely.

Though it’s Evangelicals and Catholics that seem to have that racial divide. It’s equally baffling there…we have the same Pope, the same theology, the same leadership…but radically different takes on important issues. I will read your other post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gronda, this one is a not necessarily religious. It is pseudo-new outlets and their talking heads that speak to an audience that may include a high percentage of the evangelicals. The controlling fossil fuel story line dictates the message. Ministers have done a disservice when they preach on this subject, as they are largely uninformed picking up on what their party has told them. The Pope’s white paper on climate change is essential for all religious people to read. Oh, and by the way, he is a scientist by training. Keith

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Keith,

As a person of faith, I know that you have to be troubled by all of this tie regarding the denial climate change science between too many White Evangelicals and the fossil fuel industry, as being financially motivated.

Wait until you read my 8th blog that I just published. It will make you sick. I found it revolting.

Hugs, Gronda.

LikeLike